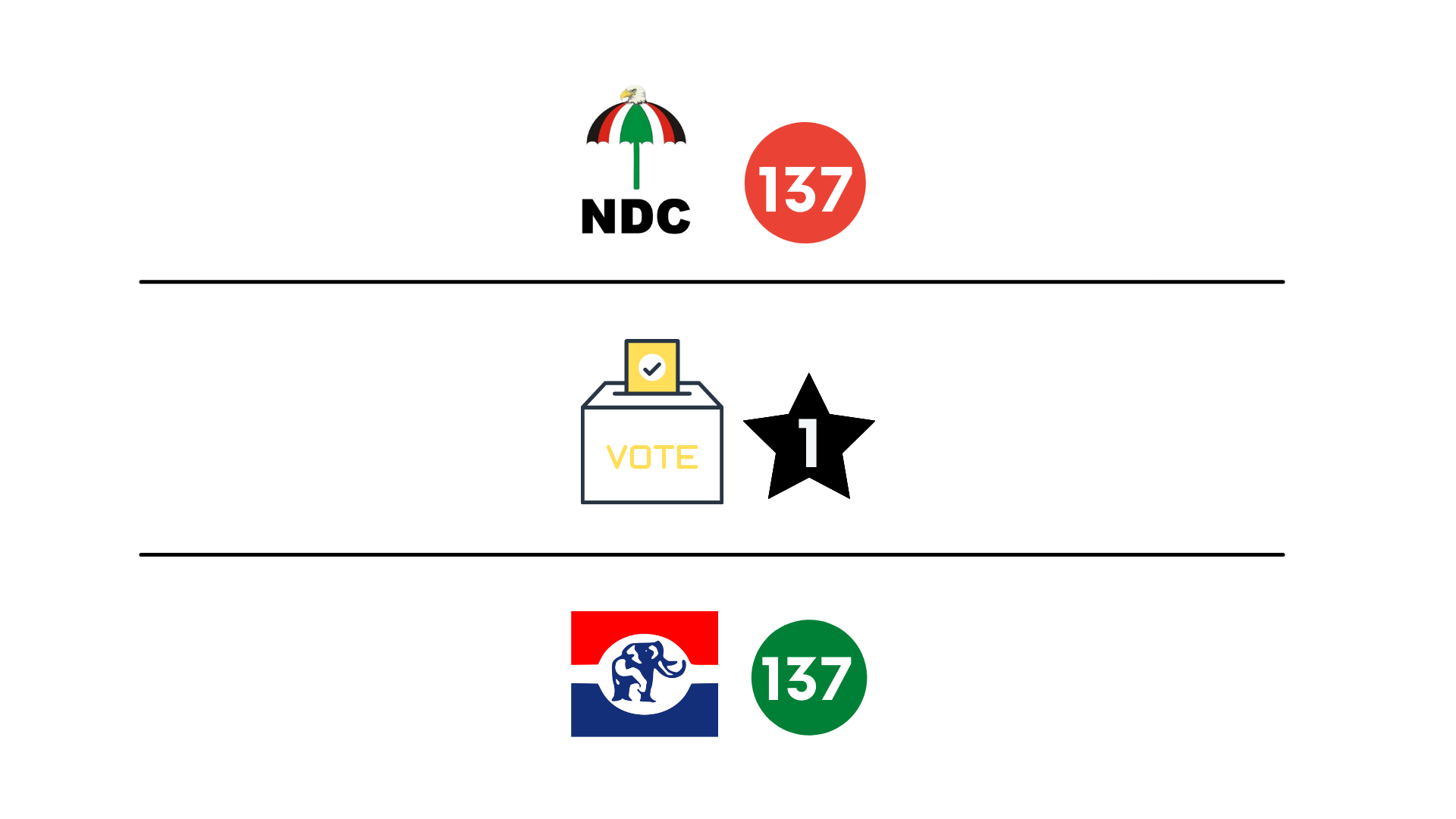

The 2020 elections in Ghana was historic not just because of the record voter turnout but because the parliamentary results ushered in a new paradigm in Ghanaian politics; of the 275 seats in Parliament, both parties won 137 each and the final seat went to an independent candidate. We consider the opportunities the current party organisation in Ghana’s Parliament provides in the quest for truly representative, constituent-centred legislatures.

Mill says of the proper functions of representative bodies is that “the whole people, or some numerous portion of them, exercise through deputies periodically elected by themselves the ultimate controlling power, which, in every constitution, must reside somewhere”. The realisation of the donor-donee relationship that should properly characterize the relationship between members of legislatures and their electors has been the challenge of modern democracies.

Rules of party discipline, in established and fragile democracies alike, have often succeeded in tilting the scales of representatives’ priorities in favour of the political parties upon whose platform they ascended office over the interests of their constituents.

To wit, five of the seven Republican senators who voted to impeach former US President Donald Trump have been censured by the parties with a censure vote scheduled in March for Senator Susan Collins. In the UK, incessant attempts by the Johnson administration to side-step Parliament during Brexit negotiations were reminiscent of, according to some commentators, Lord Hailsham’s fears of the UK descending into an “elective dictatorship”. This article considers the opportunities the current party organisation in Ghana’s Parliament provides in the quest for truly representative, constituent-centred legislatures.

A necessary starting point to understand the significance of the current composition of Parliament is to appreciate the circumstances that led to the drafting of the constitutional provisions pertaining to the legislature as found in Chapter 10 of the 1992 Constitution. Ghana resumed a brief dalliance with presidential democracy following the adoption of the 1979 Constitution under which Dr Hilla Limann was executive president.

However, the 1979 Constitution did not replicate the vast legislative and executive powers that were vested in Dr Nkrumah under the Republican Constitution of 1960.

Thus, despite the People’s National Party commanding a slim majority in Parliament with 71 of the 140 seats, the Limann administration could not avoid “the Achilles’ heel of presidential democracies”, executive-legislative deadlock. The economic downturn and collapse of state services which was occasioned by the stagnation of government business will later form the pretext of the Provisional National Defence Council’s (PNDC) 31st December coup.

Eventually, when the PNDC resolved to revert the country to constitutional rule, it was necessary to insert a provision in the new constitution to ensure government business was not stymied. To cure this deficiency, the Consultative Assembly that drafted the 1992 Constitution decided to adopt the fused elements of parliamentary democracy while maintaining the executive-legislature distinction that defined presidential democracy thereby producing our hybrid system. Article 78(1) of the 1992 Constitution subsequently mandates a majority of Ministers of State to be appointed from Parliament to facilitate government business in the Chamber.

The hybrid system has been a success to the extent that it was created to make the lawmaking process seamless as consecutive Parliaments in the Fourth Republic have successfully enacted several landmark statutes which have, for better or for worse, changed the fates of our country. Nonetheless, the current constitutional arrangement has fomented a “winner-takes-all” style of governance wherein the legislative, oversight and accountability functions of Parliament have been traded for merely rubber-stamping the will of the executive.

In this respect, the opposition is empowered to go beyond mere cosmetic displays of disapproval and ensure that every piece of legislation that emanates from Parliament represents the comprehensive and considered opinion of our elected representatives.

Within this context, the December 7, 2020 elections were historic not least because of the record voter turnout it recorded but because the parliamentary results ushered in a new paradigm in Ghanaian politics, one which the Fourth Republican Constitution could not have envisaged: of the 275 seats available, both parties won 137 each and the final seat went to Hon. Andrew Amoako Asiamah, the independent candidate from Fomena who was a member of the previous Parliament on the ticket of the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP).

After a heated swearing-in session, it was decided between party leadership to have Rt. Hon Alban Sumana Kingsford Bagbin, a veteran member of the Fourth Parliament from the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC) assume the position of Speaker, Hon. Joseph Osei-Owusu of the NPP as First Deputy Speaker and Hon. Asiamah as the Second Deputy Speaker. This composition of the Eighth Parliament will be relevant for furthering the interests of constituents in the following ways.

Due to the Second Deputy Speaker formally aligning with the ruling party, committees will be composed based on the approved ratio of 138:137. Nonetheless, this slight lead is unlikely to affect the equal representation of both parties on committees nor the distribution of committee leadership positions among the 4 Standing Committees and the 16 Select Committees whose leadership is not pre-determined by the Standing Orders of Parliament. The equal composition of the Appointments Committee and the Business Committee will seem to affirm this position.

The significance of this development is, perhaps, most apparent in the ongoing vetting of the ministers-designate as members from the opposition will have equal input to determine the principal officers in this administration. Hence, whereas the Joe Ghartey Committee which cleared Hon. Boakye Agyarko of corruption charges during the 2017 ministerial vetting was itself accused of being a show trial, the opposition in this Parliament will be empowered to thoroughly investigate any such allegations and ensure transparency in the vetting process.

Of more significance is the impact this arrangement will have on the primary function of Parliament, lawmaking. It has been the norm within this Fourth Republic for the executive to bulldoze controversial bills through Parliament amidst criticism from the opposition hence the oft-quoted slogan “the minority will have its say but the majority will have its way” has been a favourite amongst Speakers in this Republic. The opposition has usually responded by boycotting votes and staging walkouts.

To wit, the erstwhile Seventh Parliament recorded a total of eleven walkouts with the latest being the passage of the Agyapa Royalties deal in August 2020. The current composition of Parliament obliges the opposition to put their money where their mouths are and block the passage of any law which it deems not to be in the public interest. The corollary to this is that it will encourage the government to mount formidable defences for the Bills they introduce and foster more constructive debates rather than laying Bills in Parliament as a mere formality.

In this respect, the opposition is empowered to go beyond mere cosmetic displays of disapproval and ensure that every piece of legislation that emanates from Parliament represents the comprehensive and considered opinion of our elected representatives.

A related point is the control of budgets. An important function of legislatures is to control government expenditure and ensure the public purse is being put to good use. This is done by the power to approve budgets being vested in the legislature and the activities of Parliamentary Oversight Committees such as the Public Accounts Committee in Ghana and the United Kingdom. The performance of this function in the Ghanaian Parliament has been underwhelming.

Successive governments have managed to pass budgets despite disapproval from the opposition. Indeed, the first national budget presented in the previous Parliament was passed despite being boycotted by the minority. Additionally, recommendations for sanctions to be imposed on persons found culpable of some economic malfeasance by the Public Accounts Committee are not usually implemented due to executive inertia. Consequently, the current composition of Parliament will allow the opposition to streamline the budgets of various MMDAs to prevent over-expenditure.

Moreover, the opposition may leverage its numbers to ensure that recommendations from the Public Accounts Committee are implemented by the relevant executive bodies. Nonetheless, we must not lose sight of the fact that whichever triumphs we achieve in this Parliament are a result of the peculiar results of the previous election and will not extend to the ninth Parliament. Indeed, ongoing challenges to three Constituency results might suggest that the current composition will not even subsist in this Parliament. Essentially, it is of paramount importance that permanent provisions are made to reign in the excessive powers of the executive and promote a truly responsive and representative Parliament.

Author

Sam Kwadwo Owusu-Ansah | Research Analyst, Transnational Policy | s.o@borg.re

The opinions expressed are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of borg.

The ideas expressed qualifies as copyright and is protected under the Berne Convention.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is notified.

©2021 borg. Legal & Policy Research