The first part of a two-part series on - A Short History of Tribal Stereotypes in Nigeria.

Ideas.memo | Ilamosi Ekenimoh

Tribalist: /noun/ an advocate or practitioner of strong loyalty to one’s own tribe or social group; one who believes in tribalism.

It is an unwritten rule in an invisible book that every tribalist tale about Nigeria begins in 1914 with Lugard’s amalgamation. And if the amalgamation is not the beginning, then, it is the story itself. And if not that, it is ultimately and inevitably its conclusion.

The story often narrates a tale of real events with tragic consequences: an amalgamation, a call for independence, an economic boom, a military coup, a civil war, a pseudo-democracy, and ultimately a failing state.

The story or history of tribalism in Nigeria is curiously the same, no matter its minstrel. The same re-hashing of events from the perspectives of various eyes. The only difference is that often, the roles of hero and villain rotate with the ethnicity of the narrator.

Tribalism in Nigeria is an elephant at a tea party. It is constantly talked about, talked at, and pointed to and yet nobody discusses why it is at the party in the first place and how the hosts can get it out, and if it is solely the hosts’ duty to get it out. Anybody who mentions it is immediately boring, repetitive, and unoriginal. When it moves, however, the carefully constructed party comes crashing down.

Tribalism is a constant thread across all topics in Nigeria: football, politics, religion, employment, economics, entertainment, movies, and reality TV shows. It explains how Nigeria lost the match to Argentina in 199-never because our captain was changed last minute from a man in X tribe to a man in Y tribe. It explains how when one person from tribe X expresses a negative personal opinion about a person from another tribe, the logical reaction from said other tribe is to denigrate every person from tribe X.

It explains to you the concept of Delta-Igbo, and how the people so-named are not fully accepted by either of the two ethnicities. It explains to you why a church whose name literally translates to universal has a diocese in Nigeria that petitioned to replace a Vatican-appointed Bishop because he is of a different sub-ethnicity. It explains why some Nigerians describe themselves by their ethnicity first, and their nationality only when necessary.

Ignorance is Strength

Tribalism: /noun/ a set of patterned responses to the sources, concomitants, and consequences of specific changes.

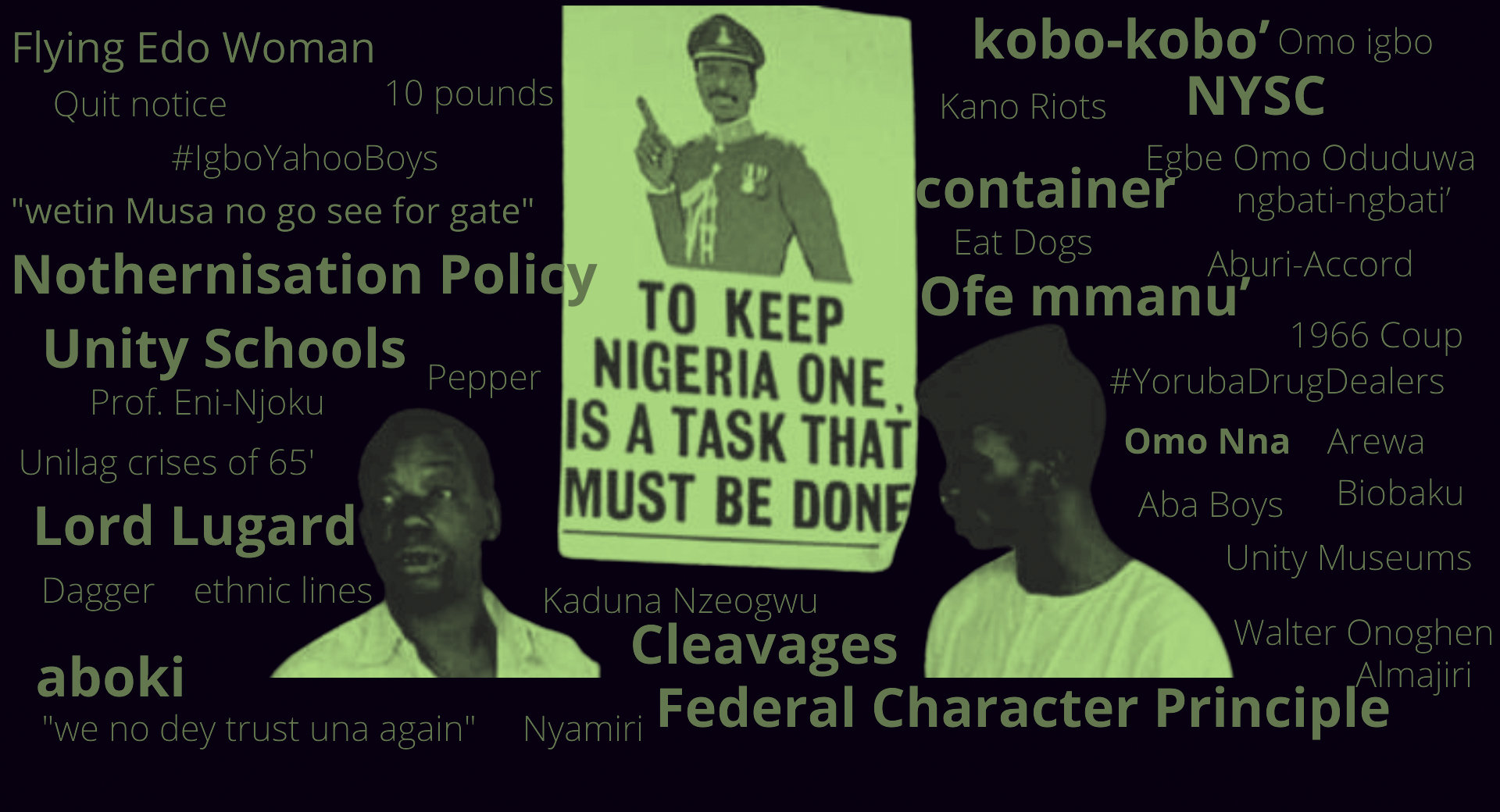

One of the many histories of tribalism in Nigeria begins with stereotypes: the naïve northerner, the brash Yoruba man, and the avaricious Igbo man. All of these rank second to the ultimate and the most persistent of all stereotypes: that all Nigerians fall into one of these three categories. These stereotypes have their origins in Nigeria’s history and are creations of multiple interactions and stories spanning decades. But one problem with stereotypes, is that they don’t change, even after the people and circumstances that created them do.

Another problem with stereotypes is that they often feature in casual interactions amongst Nigerians. And, in the event of a conflict, things mentioned in jest are flung about as absolute truths and accepted as such by members of the pitching team. Consider name-calling, a derivative of Nigeria’s culture of stereotyping; and how terms often coined in ‘humour’ enjoy popular usage. For example, ‘ngbati-ngbati’ is Nigerian popular lingo that mimics Yoruba people, and their alleged frequent use of the word nigbati, which means ‘when’.

Even if the term is an innocent attempt at humour, it displays a determined ignorance of the Yoruba language. The word is nigbati, not ngbati. and when it is used in popular references, it is derogatory; used, according to Ifedayo Adigwe Akintomide, to indicate that someone is ‘saying nonsense’, or is talking too much, as Yinka Bamgbelu illustrates. Similarly, ‘kobo-kobo’ is used in reference to is the smallest form of the Nigerian currency, and denotes a willingness by easterners to do morally questionable acts in exchange for money no matter how small. The word ‘aboki’ etymologically means ‘friend’ in Hausa but has been used in more recent times to ascribe simple-mindedness to people from Northern Nigeria.

There are more terms with complicated nuances of meaning: ‘Ofe mmanu’, which literally translates to ‘oil soup people’ in Igbo, refers to Yoruba people and their supposed fondness for, well, oily soups. ‘Nyamiri’ is a word of much-contested origins. All parties accept it has something to do with asking for water, but both Hausas and Igbos seriously contest who did the asking and receiving. Nevertheless, the term is largely understood to mean ‘infidels’ and is used by northerners in reference to non-northerners.

The contested origin of ‘Nyamiri’ illustrates how, as one famous Nigerian put it, ‘the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make the recognition of our equal humanity difficult. They emphasize how we are different, rather than how we are similar. They make one story, become the only story.’ The single-story here is of cooks, maids, cleaners, gardeners, gatemen, and chemists. And on the other hand herdsmen, internet fraudsters, smugglers, kidnappers, and drug dealers. And on the other hand, of billionaires, one for each of our major ethnic tribes. These stories rarely intersect in the minds of the people who tell them. They are separate, tangible things. Parallels that cannot exist in the same conversation. Things that are not seen as existing at the same time.

A person interviewed for the purpose of this article theorized; the average Nigerian man has no problem with his neighbour, whether from his tribe or not. Our houses, other movable property, and in fact our very lives are safeguarded by men from the North we hire as Gatemen (read Herdsmen). When ill, the average Nigerian runs to his local chemist of eastern descent, trusting him to save his health, and by extension, his life (read internet fraudster), those who could afford to still refer to the cooks of Calabar fame (read illiterate), it is the rich that have that problem. This statement, though stereotypical is also correct.

Another Nigerian notes, ‘tribalism and religious bigotry in Nigeria only exist among the middle and lower class, those who are truly rich and powerful don’t care.’ This is also true and yet is the complete opposite of the first statement. So, it would appear that the average Nigerian; particularly of the middle and lower class is not tribalist on the principle of it and is at the same time its most steadfast custodian. In simpler terms, we love to hate it.

Stereotypes and their derivatives continue to fuel Nigerian tribalist culture, and it is because they have been so casually treated that they have become so easily acceptable.

The curious thing about tribalism is that it is often more about the feeling of communality than actual community. Meaning, one might not feel a strong sense of kinship and/ or identity with clansmen connected to your ethnic group, or your ethnicity in general, but in the event of a conflict or foreign scrutiny, you will defend it to the last. It is the same way that many Nigerians feel negatively about Nigeria but will defend it to the death if insulted.

For example in 2013 amidst reports of calls for the Minister of Aviation, Stella Oduah to resign due to corruption, misappropriation of funds, and other charges, a protesting group called the Igbo Progressive Union speaking in defence of the minister at the Akanu Abiam International Airport - under construction then, stated ‘before she came into office we were hearing about international airports, but today it has become a reality in Igboland, we are ready to swim and sink with her. Nigerians become all too willing faceless men, eager to execute the command of the many-faced god that is tribalism.

Stereotypes and their derivatives continue to fuel Nigerian tribalist culture, and it is because they have been so casually treated that they have become so easily acceptable. Our deliberate ignorance of the consequences of our actions allows history to repeat itself until finally, the lesson is learnt.

Freedom is Slavery

Tribalism: /noun/ a form of political ideology

While the mistrust between tribes in Nigeria may have long since stemmed from pre-colonial interactions between ethnic groups, this mistrust is clearly traceable to the first origins of the country and is visible in its politics past and present. From the ‘divide and rule’ colonial policy, which plagued Nigeria’s infancy, to the more tawdry rhetoric of the Fourth Republic, tribal sentiments have seemed often to arise when there was something to be gained by a small faction, from causing division amongst the rest of the country.

The modern political history of tribalism in Nigeria begins in 1946, with the adoption of regionalism. But it is in 1963 that the tale finds its head. Nigeria, freshly independent of indirect rule, was brimming with potential, and an eagerness to make something of itself while the world stood captive audience.

For ease of political administration, The Azikiwe government split the country into the Eastern, Northern and Western regions, each region occupied by a major ethnic group. Political power was thus regionalized, and political parties, recognizing their regional bases as their only and proper sphere of political action established themselves accordingly.

Thus, creating a clear link between ethnicity and political power, for the first time in our modern history, independent of foreign influence. Thus, extreme regionalism became the main characteristic of the first republic. The slogan was East for the Easterners, West for the Westerners and North for the northerners. ‘Nigeria for Nobody’, as Rina Okonkwo states.

The Action Group (AG) was dominant in the mainly Yoruba speaking Western Region and headed by chief Obafemi Awolowo. It enjoyed the support and patronage of the Egbe Omo Oduduwa, a Yoruba-centric society and pressure group. The National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC) was dominant mainly in the Eastern Region, though enjoying support from politicians such as chief Adegoke Adelabu and societies like the Ibo Union.

The Northern People’s Congress, unpretentiously named, had its stronghold in the Fulani/Hausa tribes and dominated only northern Nigeria. Regionalism, thus, for the first time in our modern history, established a clear link between ethnicity and political power. It is both curious and unsurprising to note that all existing political parties in Nigeria now are amalgams and mutations of this first set of political parties.

tribal sentiments have seemed often to arise when there was something to be gained by a small faction, from causing division amongst the rest of the country.

In order to properly implement the idea of regional governments and the even grander idea of parliamentary government, it was decided that a national census be held to determine the country’s total population. The population figures would, in turn, determine parliamentary representation, revenue allocation, and employee distribution in the civil service. In essence, because the regions were organized along ethnic lines, the census would determine which ethnic group was to control Nigeria.

It had long been a sentiment held by the eastern and southern leaders that the British had established prior governance in Nigeria to be Northern favoured by virtue of population. An opinion that was strengthened through events like the Kano riots of 1953. The census could mark a turning point. Thus, began an intense campaign in the western and eastern regions, and signs went up on major highways, with warnings such as ‘Don’t be left out’.

Preliminary results showed that between 1953 and 1963, the population of northern Nigeria had gone up by 30 percent from 16.5 million to a respectable 22.5 million. Some parts of the East recorded a staggering population increase of 200 percent, and the remaining parts of the East and the West recorded a reserved 70 percent increase.

Northern leaders were understandably aggrieved by the situation. The results were reviewed solely by the prime minister, Sir Tafawa Balewa, and a new census date was fixed for the next year in 1963. This time, the population in northern Nigeria had increased to a sizeable 80 per cent, making the population of the country 31 million strong. Which was at the time larger than any other country on the continent, earning for Nigeria an unquestionable reputation as the giant of Africa.

Further censuses in the country since then have followed the same vein, marred by irregularities and impossible numbers. Nigerian historian, Ed Keazor, reports that on the eve of the 1951 Western Region elections, it appeared the NCNC would ‘overwhelmingly’ win elections in the Western region. Led by Chief Obafemi Awolowo, the Action Group sought to convince the smaller independent parties within the region to form a tribe-based coalition, whose total votes would outnumber the NCNC’s.

Since then, politics in Nigeria has been a carefully concocted cocktail of ‘Do me I do you’, with a splash of thou shall not dominate us in our own land or dominate us at all. Each major tribe seemed to believe that the other two major tribes were collaborating with each other against them. In his 1953 speech - ironically on a perceived Northern Secession, Nnamdi Azikiwe highlighted the ‘indissoluble union that nature has formed between it [the North] and the South’.

In referencing the East as a separate entity, he noted that if the British left Nigeria to its fate, northerners would not continue their uninterrupted march to the sea as was prophesized years ago because; ‘as far as I know the Eastern region has never been subjugated by any indigenous African invader…’.

One of Ahmadu Bello’s lasting legacies on the Internet is an interview clip that begins with a question to the northern premier about a seeming ‘obsession’ with Igbos in the Northern Region of Nigeria circa 1962. The northern premier, very similar to the South African Minister of Police in recent times, stated that the problem with the tribe was their (the Igbos’) need to ‘dominate’, or ‘monopolize’ work areas.

The Saurdana’s justified his views by arguing that there were educated northerners fit for civil service, who were not being employed in the Northern Region’s Civil Service. He stated that upon his assumption of service, there weren’t up to ten northerners in the Northern Civil Service.

To solve this problem, he created a northernisation policy that mandated all important posts would be held by qualified northerners, then, in order of priority; an expatriate or a Southern/ Eastern Nigerian, both on contract basis of course) where there was no qualified northerner. When asked, in the concluding part of the video if this policy was not dangerous to Nigerian Unity he answered ‘it might, but…are there northerners employed in the East or the West? The answer is no and if there are, maybe ten labourers employed in the two regions.

To note, this video has been clipped and renamed: ‘Why Igbo is being hunted by everyone’ and ‘the Northern Agenda’. Nigeria had around that time implemented a Nigerianisation policy; no Foreigner would be employed in the Nigerian Civil Service where there was a qualified Nigerian. The policy received tremendous success in the South but not in the North for obvious reasons.

As we admit that our founding fathers built the pillars upon which this country stands, let us also admit that the pillars are faulty, and their foundations unsure. To deny the participation of Nigeria’s post-independence leaders in fostering national division within Nigeria is to deny history. A good number of this first generation of politicians spoke multiple Nigerian languages and schooled in multiple regions of the country, and often spoke on the need for national unity.

For as many schemes as they had to foster this unity, they had actions that negated its existence. It is almost as if, though they acknowledged the existence of the problem, they were at a loss on how not to participate in its development. A predicament many Nigerians face today on the issue of corruption—and every other issue that currently plagues Nigeria.

The opening lines of the first Nigerian Anthem; Nigeria we hail thee our own dear native land, though tribe and tongue may differ in brotherhood we stand - could not have been farther from the truth in the country’s First Republic.